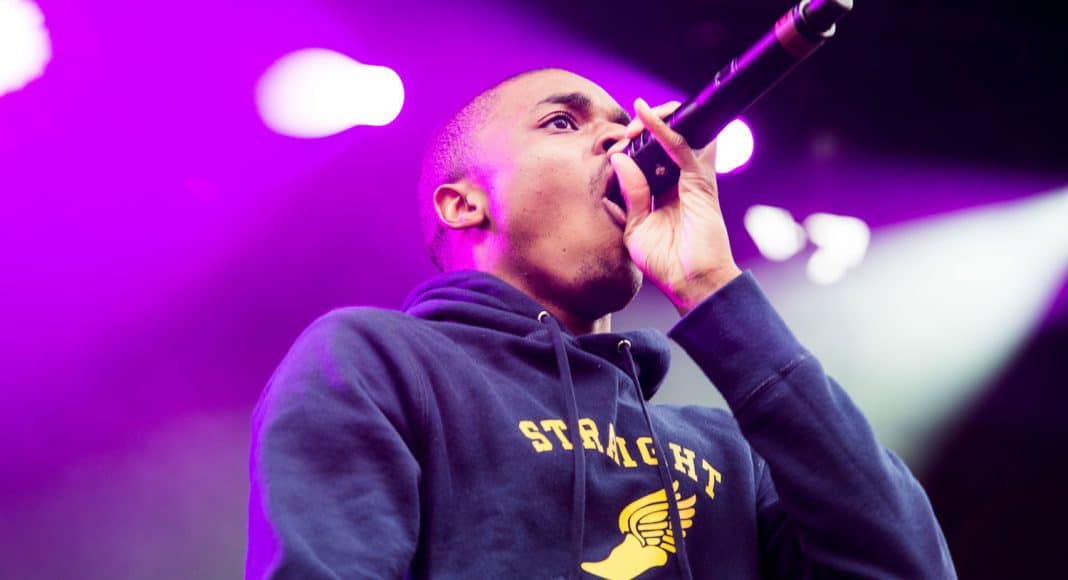

Few would accuse Vince Staples of having a big head. You wouldn’t suspect so, anyways. But at 23 years, Staples carries with him an air of living multiple lives. He’s a rapper for start, a very adept one at that, but his career began out of necessity to leave his 2N Gangsta Crip past. His rhymes weave with such earnest bluntness and a conflicted heavy heart. On “Like It Is” from his Summertime ’06 debut album, he rapped: “No matter what we grow into, we never gon’ escape our past.” Pretty bleak outlook for a then 21-year-old kid.

His music often sounds like gangsta rap, but with none of the bravado. There are no heroes in Vince’s stories. “Nate,” a hard-eyed ode to his father locked up when Vince was a first grader, succinctly sums it up: “Knew he was the villain never been a fan of Superman.”

In online circles most know Vince as a funny man. And for good reason—dude’s hilarious. His caustic wit and no bullshit demeanor heard in his raps carry over to his jokes. There’s his “Ray J is a top 5 west coast rapper” legitimate (once-you-hear-it) theory and how Sprite could end rap beefs. GQ partnered with him for videos even; proof enough his jokes are lucrative online. But he blasts internet culture routinely and threatens to leave the online world just as frequently.

Vince Staples could be high on himself, but he chooses levelheadedness at all turns is what I mean. To NPR last year, he said “My job is not for sales. My job is to keep my sanity.” From the outside, he seemed to be succeeding.

So why did this even-keeled, anti-rap rapper Vince Staples go ahead and decide to inflate his head? Especially a guy who boasts about never drinking and never smoking? Had something changed, had he succumbed to the fame, fast women, fast cars?

His recent Prima Donna EP features an artificially big-headed Vince on its cover. That big head tilts sideways, too big for its body, the way a baby’s head is. The expression’s deadpan, bored, perhaps numbed to pain, fame, and everything in between. He just doesn’t seem to give a shit anymore.

The EP begins with a bang. Vince sings a downright lugubrious version of “This Little Light of Mine,” prior to a gunshot going off. It’s a suicide and this character’s light has been extinguished. Only after a few listens do you realize Prima Donna tells its story in reverse order: A rapper achieves stardom following a successful banger (“Big Time”), establishing a bad-ass persona of some kind. This rapper starts to believe he is his persona (“Prima Donna”), but can’t duplicate the glory, skidding into a macabre insanity. Listening to the EP in reverse order, the gunshot almost comes as relief, putting this character out of his misery.

The music marks a leap in artistry and complexity for Vince. He spits furious after furious fusillade on tracks like “Loco” and “War Ready” while deftly navigating chaotic, bust-your-head-open production, thanks in bulk to DJ Dahi and one-time Kanye mentor No I.D. Special recognition goes to James Blake and the head-bopping “Big Time,” surely the hardest beat Blake’s ever created (that retro video game sample during the bridge drives me insane).

The emotions, the journey told on this EP feel personal, and Vince’s appeal has always been his personality, hilarious and candid even trapped within violence and drama. He never postures and almost ruthlessly mocks rappers who do. “I ain’t paying homage to nobody with no bodies,” he raps on “Big Time.” So again: Why the big head, Vince?

Vince also released a short film, also called Prima Donna, which he wrote, to coincide with the EP. It opens with Vince, again with that big head, bobbing between two twerking booties. He doesn’t appear happy. But it’s part of a music video shoot for “Big Time,” the director yells cut, and Vince’s head shrinks back to normal. He leaves the shoot and the film follows Vince’s descent into madness: cab drivers sing his songs without prompting to him, a woman dances and gropes him on an elevator ride, screaming fans materialize around corners to glimpse him.

In his hotel room, the four walls collapse as the hotel attendant pounds on the door, and an audience rips open the doors, demanding more Vince. You get the sense Vince believes this is how outsiders see him, the fame-hungry rapper, despite insistent evidence to the contrary. Just like listening to the EP backwards, when the gunshot fires, it relieves as much as it startles.

But Vince shoots a mirrored image of himself. The camera rushes into the destruction, passing through a stage, until it returns to an earlier shot of Vince laying on his back, staring up at the sun amidst idyllic trees and fallen leaves. Blood pools around his head, so viscous and vibrant, and the film cuts to black.

A slew of visual albums and/or short films have released in 2016. As the streaming wars heat up, and more great music releases, artists almost need to go, well, artsy to demand your attention and respect. Frank Ocean went full-blown pretentious art kid. Radiohead got Paul Thomas Anderson. Kanye invited you into his laboratory to experience his mad genius process alongside him. Rihanna pulled us in further by receding more, her enigma growing. Drake (kind of) did his same thing and was lambasted.

But of all the side projects, of all the rollouts to the main meat that is the album, I’ve only returned to Beyoncé’s Lemonade visuals and Vince’s short film. Beyoncé invites listeners in, exposing her story of the backstage drama and messy relationships we’ve all heard/suspected was going on. Plus, who am I kidding: it’s pure ecstasy watching Bey smash that bat around.

Vince is different; he’s pulling back a curtain we never knew was there. The conclusion reached is twofold: he’s playing out a version of the rapper he could’ve been, a character he could still be. You start wondering if part of him wishes to be that guy now. And that this whole artistic exercise was a mean to killing off that undesired part of himself.

That’s all speculation, though. Vince Staples remains that clear-eyed, unpretentious spitter rap needs. It’s a form of hip hop that might never make him a superstar; it’s too honest, too personal. Vince will likely never be a real prima donna. But, man, it sure was fun to pretend.