I’ve always believed in a classical education. That’s why, when my son, Eamon, was 10 and showed a curiosity about music, I turned him onto the Sex Pistols. I had no one to blame but myself when he played Never Mind the Bollocks 17 times a day. By the time he was 18, he was fronting a band and headed to NYU to major in The Music Business. (Apparently, there still is a Business.) Resigned to what I’d wrought, I suggested last summer that he round out his schooling – by taking what I dubbed the “Roots of Rock Road Trip.”

In truth, it was a selfish proposal. For years, I’d dreamt about rambling down Hank Williams’ Lost Highway — making my pilgrimage to the Crossroads where Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil. I’d been compiling a playlist – blues, bluegrass, rhythm and blues, swamp rock, rockabilly, and other Southern specialties – that I was itching to inflict on my passengers.

Happily, Eamon and my wife, Joanna, went for it, even though we’d be hitting the blacktop in August. We flew into Memphis and rented a Plymouth Grand Voyager. We started on a solemn note, we visited the National Civil Rights Museum, where the long road to freedom is retraced in powerful exhibits culminating in the actual Lorraine Motel room where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spent his last night. Walking out of the museum, we felt it was fitting to have lunch at the nearby Arcade Restaurant, opened in 1919.

-

Related Story: End Of The World: Why Is NASA Running Asteroid Tests Drills?

“Is it true Dr. King had his last meal here?” I asked our waitress.

“I never heard that,” she said. “But he ate here all the time. He’d sit in that back booth, so he could sneak out the side door.”

“Why was that?” I inquired.

“He was always being hounded by his fans. He didn’t want to have sign a lot of autographs.”

The waitress shared many surprising things about Dr. King until we deciphered that she thought I’d said, “The King,” as in, his majesty Elvis Aaron Presley. Elvis too had been a regular at the Arcade. In fact, even as we sat in our booth, he was dining at two different tables.

For this was Elvis Week, when impersonators from all over the world come to Memphis to pay tribute to the city’s favorite son. We couldn’t turn a corner without crashing into some pompadoured gent with mutton chops — curling his lip, turning up his collar. Later that day, we stopped by the 148-year-old Peabody Hotel to watch the daily ritual of ducks waddling out of the lobby fountain and into an elevator to their penthouse. While there, we browsed through the Peabody branch of Lansky Brothers, “Clothier to the King.” The 70-year-old store was filled with Elvises, all stocking up on replicas of their idol’s vestments. Our son had no prior affection for Elvis, but he couldn’t resist buying a gardenia-print sport jacket washed up from Blue Hawaii.

That night we surrendered to the cult, heading to the gilded Orpheum Theater for the semi-finals of the 10th Ultimate Elvis Tribute Artist Contest — part of Elvis Week (now in its 40th year). I was expecting to laugh, remembering Andy Kaufman’s lip-syncing on SNL. But the Elvises who strutted onstage in white sequined jumpsuits and gold lame capes could actually sing. Naturally, Japan had produced an uncanny copy — scarf-tossing Yukihiro Nishijima. By the time I left, I knew one thing: Elvis was alive.

We packed our next two days with some of the essential Memphis experiences: Beale Street, where Louis Armstrong, Albert King, and Memphis Minnie perfected their art and where, after several decades of decay, live music again spilled onto the pavement…Sun Record Studios, where Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash had their “Million-Dollar” jam one December day…the Stax Museum, on the site of the studio where Rufus Thomas, Wilson Pickett, the Staple Singers, and Otis Redding sliced fat slabs of soul…the Rock and Soul Museum, illustrating how Memphis’ black and white musicians cross-pollinated sounds that defied racial barriers…the Gibson Guitar factory, where we saw Les Pauls being hewn….and Charlie Vergos’ Rendezvous, the back-alley, subterranean BBQ joint where the Rolling Stones once jammed.

Our blaze through Memphis finished at Elvis’ former home. Graceland has grown into an amusement complex that straddles Elvis Presley Boulevard. One of its better attractions remains the museum holding more than 20 of Elvis’ vehicles. Among them are his pink 1955 Cadillac Fleetwood Series 60 (purchased after his first pink Caddy was totaled in an accident), his cream-colored 1956 Lincoln Continental Mark II, his purple 1956 Cadillac Eldorado, his black 1960 Rolls Royce Silver Cloud, his midnight blue 1970 six-door Mercedes Benz 600 limo, his 1975 Dino Ferrari, and his recently recovered black 1973 Stutz Blackhawk, which he drove on the night of his death.

It was time to descend into the Delta. We merged onto U.S. Route 61, the “Blues Highway” extolled by Sunnyland Slim and Bob Dylan. Mississippi is a heavily forested state but, here, on the flat flood plain that flanks its namesake river, a vast mural stretched above the road – a downpour at one end, sunbeams at the other. About 90 minutes south of Memphis, we rolled into Clarksdale. The former cotton port has become the unofficial capital of the blues, thanks partly to the legend that it was here that Satan bestowed unearthly gifts upon young guitarist Robert Johnson. Several towns claim to have been the scene of this Faustian transaction. But only in Clarksdale, at the intersection of Routes 61 and 49, will you find a pole crowned with three giant guitars and a sign proclaiming this the true Crossroads.

-

Related Story: Is 16K Gaming A Future Reality Or Silly Internet Experiment?

Without question, some of the greatest blues players have lived in Clarksdale, or blown through. Checking into the humble Riverside Hotel, we learned about some of its previous guests from Zee Ratliff, who runs the place with her mom, Joyce.

“John Lee Hooker, used to play here on the front steps, “ said Zee, who had a bad leg and lovely smile.

She showed us around the one-story railroad-style inn. “This is Room 7,” she said, “where Ike Turner used to sleep. Down in the basement, Ike and his Kings of Rhythm hammered out their paean to the Oldsmobile, “Rocket ’88,” often called the first rock n’ roll recording.

“Robert Nighthawk slept in this room with his wife,” Zee said. “He kept his girlfriend down the hall.” Small wonder the Chicago-bound bluesman checked out in a hurry, forgetting his suitcase. It’s still here.

Room #2 is where Bessie Smith is believed to have died in 1937, back when the hotel was the G.T. Thomas Afro-American Hospital. An ambulance brought the Empress of the Blues here from the scene of a car accident on Rt. 61.

Photos of other guests lined the hallway — Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Muddy Waters, Duke Ellington, and John Kennedy, Jr., who passed through in 1991.

We’d come to Clarksdale for the three-day Sunflower Blues and Gospel Festival. (The 30th annual fest is scheduled for Aug. 11-13, 2017). The free fest has drawn the likes of Mose Allison, Charlie Musselwhite, Koko Taylor, James “Son” Thomas, Bobby Blue Bland, and Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant. The Sunflower and the Juke Joint Festival in April have turned Clarksdale into a destination for blues travelers, like Elvis Costello, who recorded here in 2004. But, with or without a festival, you can hear blues all year long at old and new juke joints. We hotfooted it over to the Ground Zero Blues Club, opened in 2001 by Oscar-winner Morgan Freeman and local friends. On the menu: fried catfish and smoking Kingfish – as in, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram. The husky, 17-year-old Clarksdale lad has been diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome, which in his case manifests itself in virtuoso guitar playing that’s propelled him to a gig at the White House.

Kingfish’s set — exhaustively Snapchatted by my son — was an excellent start to the weekend. The next morning, we strolled around Clarksdale. The “Gold Buckle on the Cotton Belt” looked pretty rusted downtown. But some eminent ghosts lingered around the once-jumping blocks of the New World district. Wasn’t that Sam Cooke, loitering outside the old Paramount Theater? And Son House, slinking out the Alcazar Hotel? And there was Jimmy Reed, standing in the line at the art deco Greyhound Bus Terminal.

Sprouting up amidst the boarded-up storefronts were boutiques and galleries and espresso dispensaries, many of them started by young transplants. Among those helping to revive Clarksdale was John Ruskey, an artist, writer, and outdoorsman whose Quapaw Canoe Company runs expeditions on the lower Mississippi, using gorgeous 12-person wooden vessels Ruskey builds himself.

The mighty Miss was storm-tossed this particular Saturday, so Eamon and I opted for a paddle down the gentler, pine-and-cypress-lined Sunflower River. Back on land, needing another shot of blues, we headed to the fest’s main outdoor stage. There, from 10 a.m. till 11:30 p.m., performers like Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, James “Super Chikan” Johnson, and Bill “Howl-N-Madd” Perry delivered some down-home grief counseling to a lawn filled with fans. Practically every street corner had a bluesman — sometimes better than the headliner. We were ambling down one boulevard when we heard some exquisite moaning coming out of the Delta Amusement Café. Inside, Terry “Harmonica” Bean was hypnotizing an audience that consisted of one Japanese couple….and us, once we entered his force field.

Around 10 p.m., we moved onto Red’s Lounge, one of Clarksdale’s most venerable dives. Parked outside was the tour bus of Big George Brock. Some soulful songstresses and young-blood blueshounds warmed up the audience for Mr. Brock, a husky white-suited gentleman who finally sauntered in on a cane, sat down before the mic, and uncoiled his pain. Outside, the club’s bearded proprietor, Red Padden, manned a smoker the size of the Civil War ironclad. Like the pork shoulder he was cooking, Red had a crusty exterior. But he didn’t stint on his sublime BBQ, which he plopped into a Styrofoam container next to some slaw and beans. I’d no sooner thanked him than he yelled, “Wait a minute!” – then invited me to grab a fist full of Wonder Bread.

Heartache works up an appetite. In Clarksdale, even breakfast is served with a jam. Certainly at the Bluesberry Café the next morning. The restaurant had a little stage where a raspy-throated cat explained that he could only do one more song because “I gotta get back to washing dishes.”

After I finished my two eggs and a pork-chop, I asked Eamon, “Have you seen our waitress?”

“She’s onstage,” he said, “playing drums.”

Most of the other diners were on the dance floor. Boogieing out of the restaurant, we checked out the Delta Blues Museum. Housed in a freight depot built in 1918, the museum is an arsenal of guitars, harmonicas, and clothing belonging to blues legends. I wondered if donning Bobby Rush’s signed shoes or Otis Rush’s fringed vest might awaken some latent in me. Most impressive was the reconstructed cabin where Muddy Waters spent his first 30 years on the nearby Stovall Plantation. We also poked around the Rock and Blues Museum, a labor-of-love that Dutchman Theo Dasbach installed in a Clarksdale store a decade ago. Dasbach’s 4,000-plus treasures include a 1905 Edison phonograph, super-rare 78s, and memorabilia of Chuck Berry, the Beatles, the Stones, and the Doors.

Taking our leave from Clarksdale, we drove 45 minutes south to the Dockery Plantation. The still-operating farm, founded in 1895, is often called the “birthplace of the blues” because Henry Sloan, Charlie Patton, Robert Johnson, Son House, Howlin’ Wolf, and other pioneers worked, lived, and played there. Walking among its vine-shrouded buildings, Eamon encountered a snake. His mother joked that “it must be the devil,” trying to beguile another young guitarist.

A half-hour south, we came to Indianola, hometown of one Riley B. King, better known as B.B. At the corner of Second and Church, the spot where he busked as a child, King had left his hand and foot prints in the sidewalk cement. Before his death in 2015, he used to return here every year to perform. He now rests at the B.B. King Museum. His mausoleum was closed so we contented ourselves with a nearby juke joint, the Cozy Corner Café, lured by its exterior mural of local heroes and astrological forecasts. The Cozy Corner had it all — a pool table, a bar, a pink couch, an American flag, two guys playing dominoes, and, on the juke box, Albert King promising, “I’ll Play the Blues for You.” The owners, Ronnie and Betty Ward, offered us a brownie with cream cheese frosting and some conversation about Hillary Clinton, whose poster hung behind the bar. They couldn’t have been friendlier.

We headed east, passing through Greenwood. The scene of civil rights marches in the 1960s, the handsome town has no fewer than seven Blues Trail markers, including one commemorating Robert Johnson, said to have been killed at a juke joint near the intersection of Routes 82 and 49E – poisoned by the husband of a woman Johnson had been seeing. Details of his death remain so murky that two local cemeteries (Payne Chapel and Mt. Zion MB Church) both have Robert Johnson gravestones.

We finished the day in Oxford. The University of Mississippi, battleground of integration, now features the world’s largest collection of blues recordings. The following morning, we checked out William Faulkner’s stately Rowan Oak mansion (the Nobel Prize winner’s outline for A Fable is still scrawled on the wall). We also swung by Square Books (Oxford’s literary hub), Boure (flagship of star chef John Currence’s City Grocery “dine-asty”), and Fat Possum Records (a vinyl “parlour” that includes Fat Possum’s own releases, ranging from blues patriarch R.L. Burnside to the Black Keys and Iggy Pop). We could not locate Ole Miss’ hidden marijuana farm, the only federally licensed facility for pot cultivation.

An hour east of Oxford was Tupelo, the Bethlehem of Rock inasmuch as it was the birthplace of Elvis Aaron Presley. When I visited two decades ago, I could barely pick out the one-story Presley clapboard from other humble houses on a side street. It’s since been turned into a tourist complex that includes a study center and memorial chapel. There’s also a gurgling Fountain of Life — circled by stone tablets marking the sacred chapters of the Presley saga. “1939 – Home and Car Repossessed; [father] Vernon Released From Prison.” A replica of that car, a green Plymouth sedan that transported the Promised One to Memphis, sits nearby. Our own prodigal son posed next to a reproduction of the outhouse young Elvis would have used.

-

Related Story: Inside The Fresh Toast’s Milestone NYC Media Event

Ninety minutes north we arrived in Alabama at the former Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. Night had fallen but we had to snap a few pics outside 3614 Jackson Highway, the onetime coffin factory where The Swampers rhythm section had laid down gold and platinum grooves for Lynyrd Skynyrd, Joe Cocker, Levon Helm, Paul Simon, Bob Seger, Rod Stewart, Willie Nelson, and The Rolling Stones, to name a few. The following morning we stopped at the Swampers’ original workplace, the still-operating FAME Studios — pulling into the parking lot where young Duane Allman once pitched a tent in the hope of recording with Wilson Pickett. (He succeeded.) Still operating and giving tours, FAME was the laboratory for such hit-makers as Bobbie Gentry, Bettye LaVette, Etta James, Aretha Franklin, and Drive By Truckers. (The 2013 doc, Muscle Shoals, tells the soulful saga of the rival studios.)

We crossed the Tennessee River and pushed north two and half hours to the final destination of our musical hajj — Nashville. There we did some daytime honky tonkin’ on lower Broadway. Winkin’ and blinkin’ neon beckoned us, like so many previous hayseeds, into Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, Robert’s Western World, and Legends Corner. After a few longnecks and some pulled pork at Jack’s, we rifled through the vinyl at the Ernest Tubb Record Shop, opened in 1947. I genuflected outside the Ryman Auditorium, home to the Grand Ole Oprey from 1943 to 1974 and now a showcase for such un-country acts as Coldplay to the Foo Fighters.

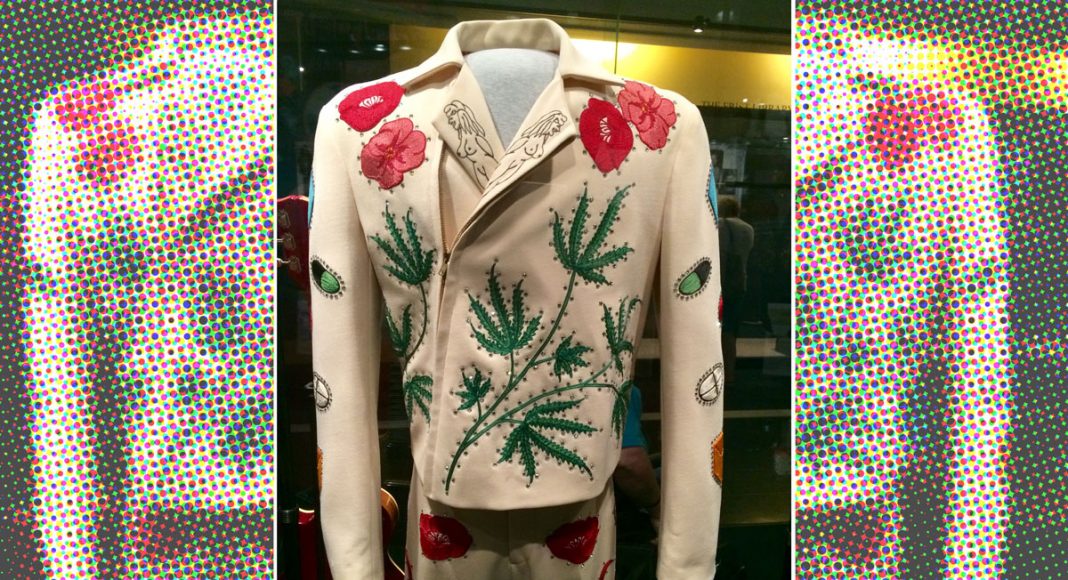

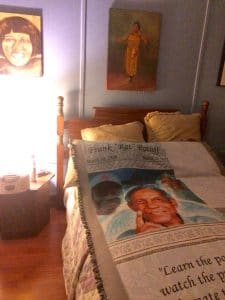

We proceeded to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, whose 2014 renovation has expanded its size to 350,000-square-feet. Even Eamon, who only tolerates country music, found the collection diverting. Among its treasures: Elvis’ Solid Gold Cadillac, glistening with paint made of ground diamonds and fish scales and outfitted with TV, phone, record player, and fridge, and Webb Pierce’s 1962 Pontiac Bonneville, festooned with silver dollars, Winchester rifles, and a steer horn on the grille. The centerpiece exhibit was “Dylan, Cash, and The Nashville Cats,” an immersive study of how out-of-town longhairs and Music City’s fabled session men devised country rock. Don’t miss Gram Parsons’ Flying Burrito Brothers suit, embroidered with cannabis leaves and poppies. (The exhibit is up till December 2017.)

Nashville has become a home to a lot of émigré artists with very little twang. No place embodies its modern sensibility like Third Man Records. Jack White’s hive of cool features a store staffed by young people in the bumblebee colors of yellow and black. Besides stocking new and classic vinyl, the shop offers a refurbished 1947 Voice-o-Graph machine. For $20, you can step into the wooden phone-booth-sized contraption and record a six-inch phonographic disc. They keep a guitar on hand, or you can bring your own. Third Man also boasts the world’s only live venue with direct-to-acetate recording capabilities. Jerry Lee Lewis, Beck, Stephen Colbert, and bands on White’s label have cut discs there. On our trip’s final night, Eamon and I stopped by Third Man’s club. The headliner was Joyce Manor, a thrashing punk unit from Torrance, California. A hundred or so kids ricocheted off the walls under a taxidermied elephant head. It was a far cry, or yodel, from the Grand Ole Oprey. Ernest Tubb would’ve had them all committed. But for a kid raised on the Sex Pistols, the mosh pit was a relief from dad’s daily roots regimen — a sign that we could finally exit the Lost Highway and head home.

The 2017 Sunflower River Blues and Gospel Festival in Clarksdale, MS, runs from August 11 to 13. The 2017 Elvis Week will mark the 40thanniversary of the King’s passing between August 11 and 19. Useful baedekers to the Deep South’s music, history, and food are Lonely Planet Road Trip: Blues & BBQ, by Tom Downs, and Memphis & The Delta Blues Trail, by Melissa and Justin Gage. You can track Blues Trail historic markers online or via a free app. The excellent American Music Triangle website helps you design your own route to the best blues, country and R&B sites in Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama.