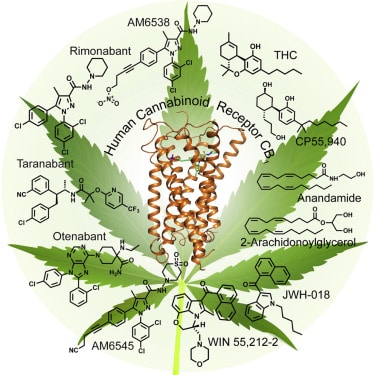

In its October 2016 issue, the journal Cell published the first atomic-level images of the human brain and cannabinoid receptor 1 (more familiarly known as CB1), the neuroreceptor that responds to THC, one of the key active ingredients in marijuana.

This is more than a cool new visual; it will help scientists understand exactly how THC functions in the body and why some molecules related to it have very different—and sometimes harmful—effects. It might also aid in designing drugs that are even more effective and more targeted than THC to treat conditions including pain, inflammation, obesity, and fibrosis.

This might not sound like sexy, cutting edge medical research, but the imaging posed a formidable technical challenge to an international team of researchers.

Neuroreceptors are structures nerve cells use to communicate with each other via electrical signals that are carried by an array of chemicals called “neurotransmitters.” You can’t just take a photo of neuroreceptors because they are far too small to be seen by lightwaves. We can only glimpse them through X-rays, which have minuscule wavelengths. And even then, we can only do it indirectly via a technique called X-ray crystallography.

The process is easy enough in theory, although fiendishly hard to execute: You bombard an atomic-level structure with X-rays, which bounce off of it in mathematically precise ways. If you record where the X-rays land, you can work backward to calculate the shape of the object that caused these deflections. Make sense?

The difficulty is that you can’t use just once object—say a CB1 receptor—because it’s still far too small. You need tens of thousands of molecules to disrupt X-rays enough to get measurable results. But if you have tens of thousands of molecules randomly jumbled together, you will get an equally random scatter of X-rays. In order to get useable evidence, every single one of the molecules must precisely aligned.

God knows how they did it, but the scientists managed to “crystalize” the CB1 receptors (that’s the lingo for putting them into a stable, uniform order) and to interpret the X-ray pattern, which proved more complex than expected. (Evidently, the receptor that’s responsible for getting us high has a suitably trippy shape.)

So, enough prelude: What does CB1 look like?

From an aesthetic standpoint, it’s a mess.

I admit that over the course of writing all these medical marijuana posts, I’d imagined my own, somewhat romanic, version of the CB1 receptor—something like an oyster mushroom or rhododendron leaf—a sort of frilly-edged cup-like frond swaying languidly from a little stalk firmly rooted in a neuron. In the hard gaze of science, however, he receptors look like an unruly wad of New Year’s Eve streamers.

A less subjective description is this: Seven transmembrane helices (think DNA) that are connected by six stiff and wiry loops (three extracellular and three intercellular, if the difference means anything to you). Somewhere deep in the structure is a funnel that receives the THC molecule. But to my untrained eyes the whole thing is an unintelligible mess.

If you’ve read this far, though, you’re clearly interested—so don’t take my word for it: Check out the images yourself and download the free article.