With no respect to Robin Thicke, who can identify a blurred line anymore? In our world full of intractable political correctness and caps-lock debates over, well, everything, you’re tempted to say blurred lines kind of don’t exist. How could they?

For example, when names of artists or activists or writers we like appear on a trending list, we hold our breath, hoping something *ignorant* doesn’t fall out of their mouths. Either that or we worry they died. Usually it’s the former, and it’s generally because that person toed that nowadays very firm line of “You’re not supposed to say/do that.” Everyone implicitly seems to understand this new boundary of acceptable behavior online, particularly if you wish to appear woke and embraced by a certain crowd. If you’re young—sigh, yes, meaning a *millennial*—you probably do. If you’re of an older generation, you’re just on Facebook. And those three rounds of Trump vs. Hillary got nothing on Facebook debates.

But these staunch attitudes also feel like a bigger and bigger lie: That we all know exactly who we are and what we believe and how we’re supposed to act. Instead, it’s like these hard edges we inscribe for ourselves—and others—feels like a harsh reaction to just how messy and distorted and confusing our lives have really become. Being alive in 2016 is really damn baffling. And everyone’s aggressively trying to pretend it’s not.

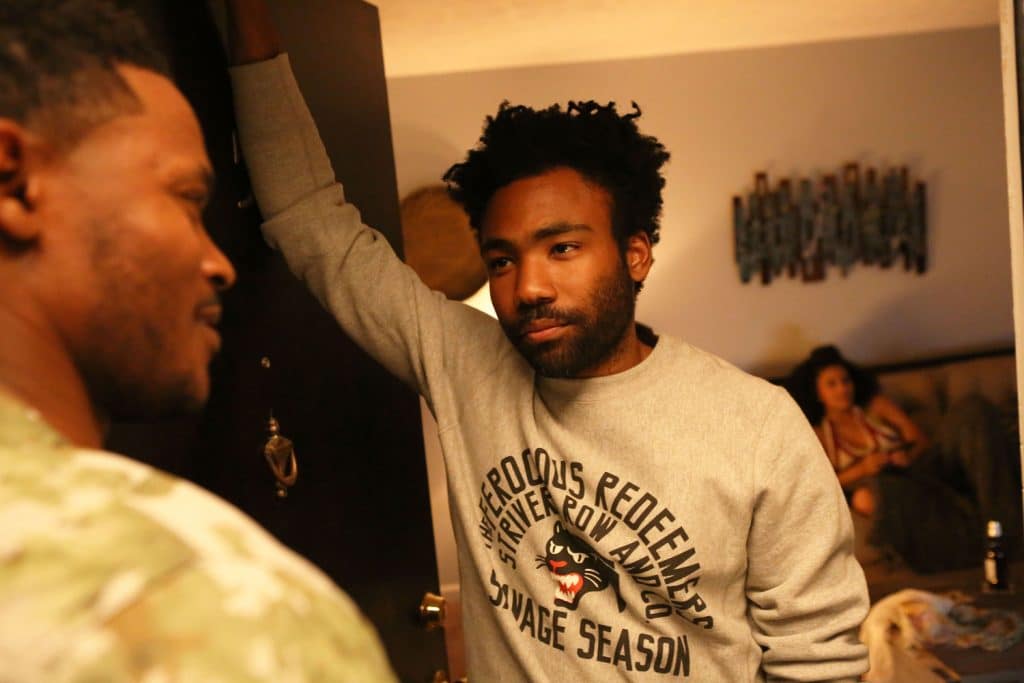

Well not everyone, I suppose. Donald Glover isn’t. Neither is his show “Atlanta,” a progressive fantasy about cousins trying to find pockets of success and solace within a broken world. It stars Glover himself, who also writes and directs, and often times depicts a sort of hyper-reality; episodes usually follow a “day in the life” of characters as more routine sitcom plot developments fade to the background. It’s also surreal: sometimes a pudgy kid wearing a Batman mask will knock on your door to see who lives there. A white aristocrat obsessed with African culture might perform spoken word poetry, filmed like it’s straight out of a Spike Lee joint. The show’s power lies in that unapologetic ethos: Like in life, anything can happen. And in Atlanta, anything truly means anything.

One of Glover’s strengths revolves around his understanding of media. When he released his Because the Internet project under his rapper name Childish Gambino, the rollout was a masterclass of building internet hype. A cryptic short film, Easter eggs hidden beneath coding in his website, some refreshingly honest Instagram posts, a screenplay deepening the story behind his record. He didn’t release an album; he unleashed a world.

He cut across with TV critics in a similar way, when he described his show as “Twin Peaks with rappers” ahead of its premiere. It’s a tag still attached to the show following its full-season run. The other line, which he’s repeated in some variation, is more complex: “I’m trying to make people feel black.” Great quotes, and his show delivers on those promises: Nothing is as it appears. You don’t understand what’s underneath the surface. Does anyone?

When we first encounter Glover’s Earnest “Earn” Marks, he’s absolutely shook. A Princeton dropout, homeless, and pretty much penniless, he’s just trying to survive. When you’re as broke and rudderless as Earn, you realize choice and joy and standing up for yourself are luxuries, not rights. His parents won’t let him into their house, and he just has to accept that. Fighting might ruin his final remaining lifelines.

Another of Glover’s talents is his physical intelligence. His character’s progress throughout this season resembles a humanity evolutionary chart: slump and slouched to start, but standing upright by the finale. That he has regained his confidence is no easy feat—often he’s within the crosshairs of the surrealist moments of the show. In the “Nobody Beats the Biebs” episode, Jane Adams’ Janice character mistakes Earn for someone else. An old colleague named Alonzo. At first Earn fights the identity, but plays along once it grants him access into the room with other agents.

As typical sitcom plots go, you keep waiting for Earn to be found out. He never is. Instead Janice accuses him, as Alonzo, as sabotaging her career and vows to destroy his. Atlanta never gives you what you expect. It subverts your anticipation nearly any chance it can without collapsing on itself.

Its funniest and most brilliant episode “B.A.N,” where Paperboi appears on the talk show Montague, pushes this to its breaking point with hilarious parody commercials of Dodge Chargers (“the official car of making a statement without saying anything at all”) and Swisher Sweets cigarillos (now sold pre-dumped!). Written and directed by Glover, it also features a segment on Antoine, who woke up one day and realized he was a white man named Harrison. He started wearing a “thick, brown leather belt and Patagonia” and practiced ordering IPAs in preparation of undergoing a “full racial transition” surgery.

Antoine/Harrison is played by Niles Stewart, the Vine/YouTube sensation Nileseyy Niles. It’s yet another blurring of these identity lines: the internet vs. reality, white vs. black, who you are vs. who you pretend to be. But is it so strange? The storyline was clearly inspired by Rachel Dolezal, who claimed herself to be “transracial.” So is Atlanta a twisted funhouse-mirror reflection of our world or an accurate portrait? That of course depends on you. How does this world look and feel to you?

Characters aren’t always how they seem on the surface. Most of what stoner goofball Darius says seems like absurd nonsense—only he seems the calmest person on the show. He never acts like someone he isn’t. He’s always Darius, regardless of the situation. Meanwhile, Earn’s baby momma Van isn’t just the nagging woman forcing Earn to face reality. She, too, must battle perceptions of her “worth” from friends and play roles unbecoming so she can make it in this world.

It’s nearly impossible not to love Atlanta rapper Paperboi a.k.a Alfred. Played by Brian Tyree Henry, he’s blunt, usually blunt-ed, but also something like a turtle—hard shell, soft underbelly. Whereas other characters embrace or (try to) dismiss the strange that keeps finding them, Alfred confronts it, all while his face carries a tone of “you’ve gotta be shitting me.” Outsiders (particularly if they’re white) see him as a rich, hood rapper—a thug. “I scare people at ATMs, boy,” Alfred says. “I have to rap. That’s what rap is: making the best out of a bad situation.”

Better his situations he has. I won’t front. That “Paperboi” record is kind of fire. I’d throw it on a playlist. But two alternate realities diverge for the character. Paperboi is blowing up. We hear his song bumping in passing cars and speakers; his growing celebrity warrants invites to charity basketball games, TV talk shows, and club appearances. Paperboi seems like a success.

Alfred, however, doesn’t always reap the fruits of his labor. Glover’s Earnest “Earn” Marks, who manages Paperboi, must scheme to get Paperboi’s song on the radio. He struggles to get the money from their club appearance. As a result, Alfred shakes down the club owner, getting what he’s been promised, but receives that old label of “thug” and “criminal” the media wants him to play. Even during the celebrity game, none of the reporters there take him seriously; he practically begs one for an interview, revealing the “real Paperboi,” and is denied. Following a beef Paperboi starts with “black Justin Bieber” (in Atlanta, anything truly means anything…), that same reporter offers a harsh perspective.

“Play your part,” she says. “People don’t want Justin to be the asshole. They want you to be the asshole. You’re a rapper. That’s your job.”

We know Justin is an asshole, though. Someone in the crowd yells, “I love you, Justin,” and he responds, “I know, bitch.” He’s not a good person underneath. It just doesn’t matter. People see you how they want to see you. Especially when you’re a black male living in this country.

The reveal comes during a press conference for Justin Bieber. He apologizes for the incident, claiming he’s turned into something he’s not. To prove it, he turns his previously backwards hat forward and reporters gasp at the change. “Wait. It’s cool. It’s cool,” he says. “This is me. This is the real Justin.”

Everyone believes the act. They so desperately want to. Their fixed reality stays the same. Atlanta shows you this time and time again. As much as things change for its characters, the world stays the same. This is by design. But one of Atlanta’s revolutionary acts is saying those blurred lines still exist. It’s up to you to see them.