Tuberculosis is a highly contagious lung disease that killed the poet John Keats, plus tens of thousands of more obscure victims of England’s bad climate and the worse hygiene of the Industrial Revolution. Because those stricken with tuberculosis would stereotypically lose their appetite then slowly waste away after taking melodramatically to their beds, the disease acquired the romantically gothic name “consumption.” But there is nothing romantic about its shattering chest pain or bloody sputum.

The advent of antibiotics in the mid-twentieth century nearly eradicated tuberculosis in the developed world. However, it resurged during the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s as one of the many opportunistic infections that dog-pilled the immunocompromised patients. Of course, in the developing world, the disease never went on hiatus, and today, new drug-resistant strains have made tuberculosis into one of the globe’s top killers.

Historically, there has been little study of cannabis and tuberculosis, aside from a few studies showing that communal smoking can spread the disease. (Pro tip: Don’t share a bong with someone who’s coughing up blood.) But this July a surprising report appeared that suggested cannabis may actually combat tuberculosis.

The cannabinoid in question is not THC or CBD—the usual suspects—or even second-stringers CBG, CBD, or even THCV or CBC. No, it’s the relatively unknown, but up-and-coming, beta-caryophyllene (BCP), which some are hailing as a miracle cannabinoid: Not only won’t it make you high (CBD already does that) but it is also abundantly available in sources other than marijuana, for instance oregano, basil, lime, cinnamon, carrots, celery, and black pepper berries—all perfectly legal and delicious!

-

Related Story: Why Won’t My Doctor Prescribe Medical Marijuana For Me?

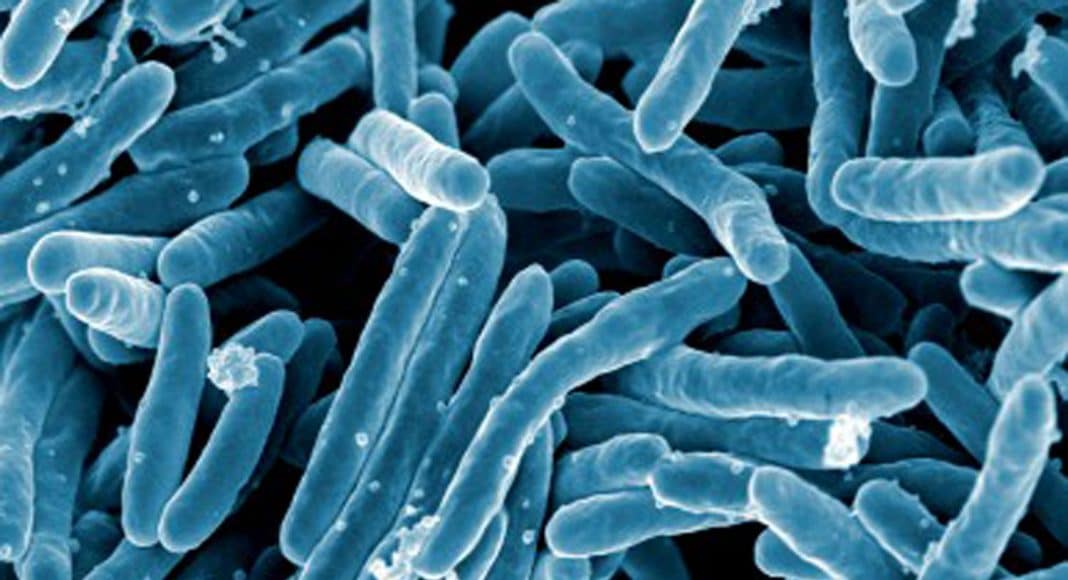

BCP doesn’t attack the Mycobacterium bovis bacillus that causes tuberculosis. Rather, it heals by restraining the body’s inflammatory response to it. At least it does so in mice. If you’ve been following medical cannabis research, you may be excused for suspecting that “inflammation” has become a meaningless buzzword. For your consideration, we offer this review that examines the deadly dual role of inflammation during a tubercular infection. The authors show, in meticulous, molecular detail, just how the body’s inflammatory immune response gets jujitsu-flipped into inadvertently killing ourselves instead of the infection. (Caveat one: the science is difficult. Caveat two: the English is downright painful.)

As always with this basic research, this is not a cure and this might not even lead directly to one. But any lead toward combating drug-resistant tuberculosis is important.