Ontario’s first legal cannabis shops are finally here. One challenge they’ll face is Canada’s nationwide product shortage. That’s despite repeated federal government assurances of ample supplies.

Cannabis shortages certainly seem to exist. Ontario blames them for its initial 25-store limit. Alberta is also restricting shop licences, while Québec limits shopping hours.

However, federal officials disagree. Bill Blair, the minister leading Cannabis Act implementation, has repeatedly said supplies are “adequate” and even “exceed existing demand.”

RELATED: Could Canada Use Nevada’s Marijuana Shortage Protocol?

Similarly, Health Canada last week claimed “there is not — as some have suggested — a national shortage of supply of cannabis.” It earlier had bragged that January’s dry (smoke-able) cannabis inventories were so large they equalled “19 times the amount sold.”

But the government’s own data shows it’s blowing smoke.

Low sales

Statistics Canada numbers show licensed retailers aren’t selling much. Only one-fifth of national cannabis spending from October to December was legal. In January, legal sales fell five percent.

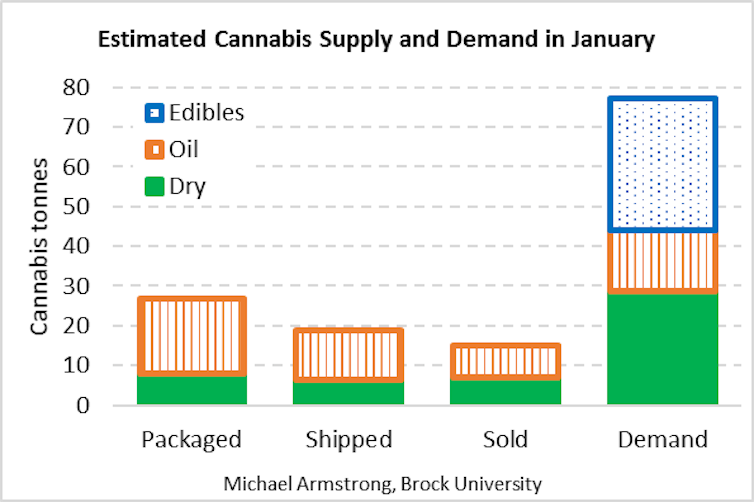

Similarly, Health Canada’s latest update indicates January sales totalled about 15 tonnes of dry cannabis and cannabis oils (1 tonne = 1,000 kg). That’s for medical and recreational products combined. By contrast, its estimate implies monthly demand is around 77 tonnes.

Cannabis oils aren’t the problem. Their sales volume rose four percent, the third consecutive monthly gain.

But dry cannabis sales slid four percent to 7.1 tonnes. That’s concerning because recreational users prefer dry products to oils. In October and November, dry cannabis captured 72 percent of recreational sales nationwide. It got 90 percent in Québec and New Brunswick.

Altogether, just around 15 percent of cannabis sold in Canada is legal. Even provinces with relatively plentiful stores have legal shares of only about 29 percent.

Such widespread weakness can’t be solely due to some provinces having “difficulties” with “distribution systems,” as Blair has claimed. But neither he nor Health Canada has offered better explanations. That department collects extensive industry data but keeps most numbers secret. It publishes only inventory and sales totals. Fortunately, we can learn much from those.

Falling shipments

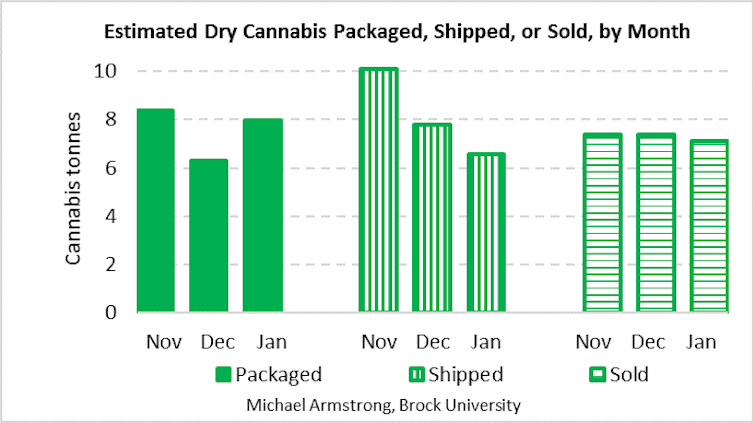

For example, in January retailers sold 5.3 tonnes of recreational dry cannabis, while their inventory decreased 0.5 tonnes. So, they must have received just 4.8 tonnes of new product from producers. (Another 1.8 tonnes went directly from producers to medical clients.)

That implies retailers didn’t sell much dry cannabis in January because they didn’t receive much. January’s dry shipments to retailers were 21 percent lower than December’s, which were already lower than November’s.

RELATED: Canadian Marijuana Shortages Could Go On For Years

And retailers got little in January because producers processed little in December. Another inventory comparison suggests producers packaged just 6.3 tonnes of dry products that month. That’s only three-quarters of November’s rate. And inadequate to support existing sales.

(It was December’s data that Blair claimed showed supplies are “sufficient.”)

This wasn’t a temporary shortfall. The average monthly packaging rate from November to January for dry cannabis products was around 7.6 tonnes.

Government smokescreens

This analysis suggests federal claims of adequate cannabis supplies are mere smokescreens for substantial shortages.

Similarly, Health Canada claiming dry “inventories” were 19 times “sales” is just smoke and mirrors. It’s correct but meaningless.

Those inventories were mostly raw material or work-in-process: unfinished cannabis drying, curing, or awaiting processing. Only 15 percent was finished product, and less than half of that was at retailers. And existing sales are too weak to be worth targeting.

(Besides, inventory-to-sales ratios indicate little about availability. In some sectors, retailers hold less than two months of inventory.)

Comparing production to demand is more meaningful. January’s dry product packaging was about 8.0 tonnes, enough for perhaps a quarter of dry demand. Combined dry and oil packaging totaled 27 tonnes, about one-third of overall cannabis demand.

There’s another reason the latter fraction is low. The federal government hasn’t yet legalized cannabis foods and drinks. Those edibles constitute 43 percent of sales in Colorado, California and Oregon. Their absence here leaves a big gap.

Stop playing games

The federal government really must stop playing make-believe about cannabis availability. Nonsensical supply claims raise expectations, and hence frustrations, among businesses and consumers.

Similarly, Health Canada must stop playing hide-and-seek with information. It collects monthly fresh cannabis production and finished product packaging data. It should start reporting them. That clarity would help producers and retailers make better business decisions.

Producers are already making progress. Canada now has 164 licensed sellers, with hundreds more reportedly on the way. Total cultivation area rose 20 percent in December alone. But it takes months for new sites to grow, process and ship cannabis to stores.

Retailers too are finally making progress in Ontario. They’ll make legal cannabis more available and therefore more competitive with black markets. Given Québec’s results, Ontario’s first shops might average around $1.25 million in monthly sales each. Individual store’s results naturally will depend on location — and on the shortages it encounters. I wish them all the best.![]()

Michael J. Armstrong, Associate professor of operations research, Goodman School of Business, Brock University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.