The legalization of marijuana in Canada comes almost a century after the drug was first declared an illegal substance in 1923, but pot didn’t explode in popularity until the 1960s when a group of rebellious people began promoting it as a shortcut to peace and enlightenment.

Concerned about the new use of this drug, in 1969, the Royal Commission on the Non-Medical Use of Drugs visited coffee shops and universities to talk to young people about marijuana use.

One student told them marijuana reveals “a greater sense of the universe.” He enthused that “things you never noticed… now jump out … and every event becomes suddenly deep.” Another touted that cannabis could be the “catalyst to the great Epiphany.”

Related: How To Approach Your Baby Boomer Parents About Weed

One participant promised “fantastic benefits” from smoking marijuana and said that it could lead to “a much better way of living.”

In short, many baby boomers believed marijuana use could usher in a new era of experience, enlightenment and joy. Half a century ago, this was utterly new to most Canadians.

Cannabis convictions soar

Convictions for cannabis went from 60 in 1965 to 6,292 in 1970. By the spring of 1970, the Royal Commission on the Non-Medical Use of Drugs suggested that somewhere between 1.3 and 1.5 million Canadians had used marijuana.

A survey of Toronto adults in 1971 showed that 8.4 per cent had used cannabis in the previous year, with higher rates among young people. Thirty per cent of people between the ages of 18 and 25 said they had tried the drug, while only 10 per cent of people aged 25 to 35 had smoked marijuana. From 1968 to 1972, marijuana use at Toronto high schools tripled.

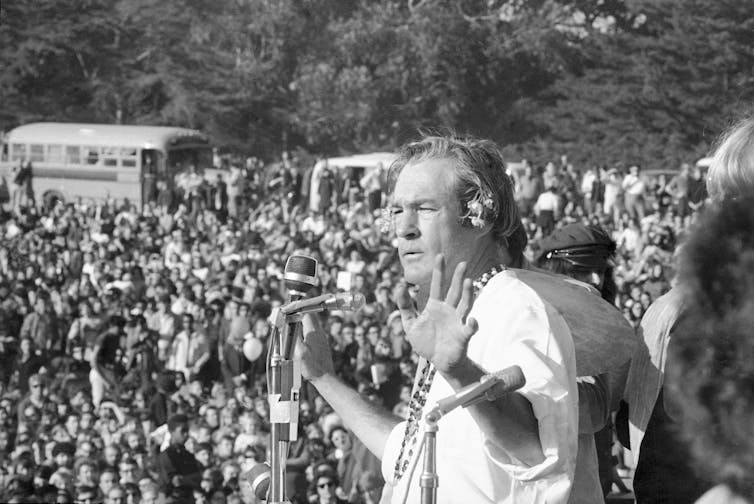

What made this new generation of young people reject the hard-drinking ways of their elders in favor of a new drug? Part of marijuana’s appeal was its illicit status — it allowed baby boomers to reject the rules of the “establishment” and the habits of their parents.

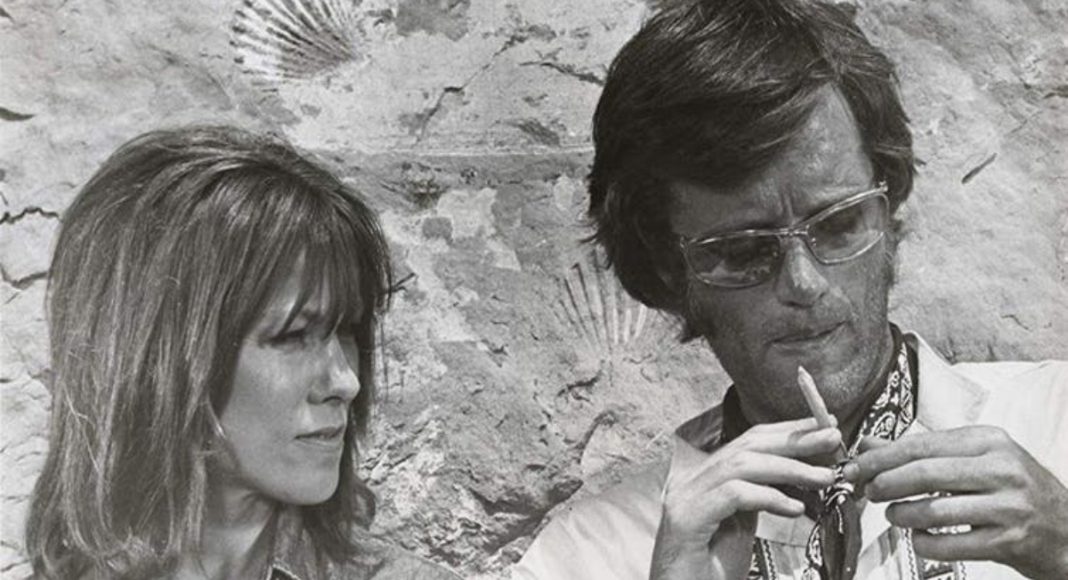

It was believed marijuana would open them to new experiences, while alcohol diminished awareness. As the LSD guru, Timothy Leary, put it in his Politics of Ecstasy, alcohol consumption brought about the “State of Emotional Stupor” while marijuana would lead to “The State of Sensory Awareness.”

Marijuana users were well aware that their parents already took a wide array of legal and prescription drugs. They were often highly critical of prescription drugs like barbiturates and tranquillizers. They believed these drugs numbed people to the injustices and inadequacies of North American society.

Promises of enlightenment

By contrast, marijuana promised to open a path to enlightenment. Many baby boomers were interested in Eastern religions and transcendent experiences. As Charles Reich put it in his Greening of America, an ode to the new generation, “using marijuana is more like what happens when a person with fuzzy vision puts on glasses.”

Reich explained that marijuana enabled people to hear new sounds in music and to visualize the world in new ways. It would allow them to understand time differently, thereby releasing them from the unrelenting demands of a capitalist society.

Other marijuana users were influenced by the popular culture of the day to try the drug. The Beatles were getting “high with a little help” from their friends. Janis Joplin spent all her money on drugs in “Mary Jane.” Bob Dylan intoned: “Everybody must get stoned.”

Drug use was also glorified in movies. The Beatles psychedelic cartoon Yellow Submarine premiered in 1968, while the countercultural classic Easy Rider came out the following year. It featured Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper driving their motorcycles from Los Angeles to New Orleans, smoking dope, taking LSD, visiting a commune and raising the ire of the establishment.

Finding a ‘groove’

From the Mariposa music festival to the coffee shops of Toronto’s Yorkville neighbourhood, marijuana wafted through the air of the late 1960s. Headshops were a vital part of the street life in countercultural communities like Vancouver’s Kitsilano. Stores like the Polevault in Vancouver featured coloured lights beaming through parachutes on the ceiling, while chairs, cushions and ashtrays invited people to stay and “groove.” Countercultural newspapers like the Georgia Straight (Vancouver), Harbinger (Toronto) and Octopus (Ottawa) glamourized marijuana in their pages.

Marijuana proponents did not persuade the Royal Commission that marijuana would usher in a new era of enlightenment. But the Commissioners were persuaded that the costs of marijuana prohibition were too high, both for individuals and the state. They recommended the laws against the prohibition of marijuana be repealed.

This did not happen, as Marcel Martel explains in his book Not this Time. Jean Chretien’s attempt to decriminalize marijuana in 2003 also failed.

Finally, more than 50 years after the “Summer of Love”, cannabis will be legalized in Canada, although the dream of marijuana’s potential to create a new society has largely passed.

Catherine Carstairs, Professor and Chair, Department of History, University of Guelph